The central section of the château of Chambord is the keep, otherwise known as the donjon.

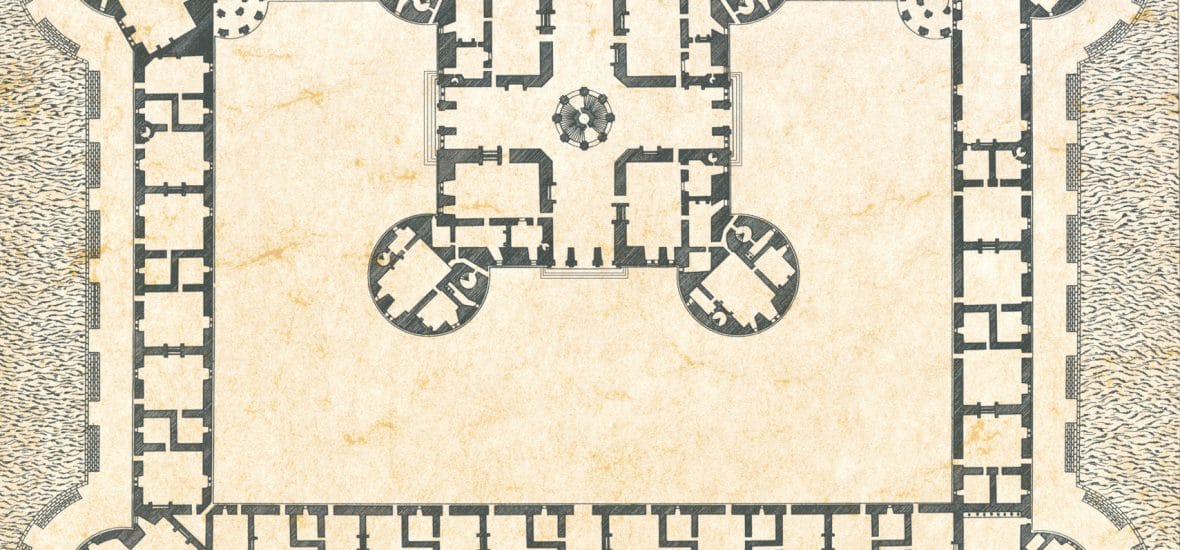

The square building delimited by four corner towers occupies the center of the present-day complex. When construction work began, it constituted the new palace of François I. It was only in or around 1526, date marking the return of the French king following two years of captivity in Madrid subsequent to military defeat in Pavia, that the edifice was complemented by two lateral buildings and an enclosure marking off the court.

The internal composition of the keep is laid out in a way never previously seen in France and presents an undeniably “Italian” aspect. It features a Greek cross-shaped centered design; the four sides of the building open up onto spacious rooms (9m wide and 18m long) forming a Greek cross. In the center rises the monumental double helix staircase. Last but not least, the cross-shaped room delineates in its angles the living quarters composed of standardized apartments.

The ornamentation of the upper parts of the keep and the château, which are riddled with chimneys and stairway turrets, recalls the stylistic peculiarities of fortified castles.

However, when the Chambord château was under construction, these traditional forms of medieval architecture had long since come to be considered as obsolete. Indeed, advances in artillery meant that by the mid-15th century, fortified castles had outlived their usefulness. That said, the persistent survival of medieval architecture in the Chambord château should not be attributed to a mistaken notion that the builders were somehow “behind the times”. Take a close look at the keep, at its corner towers, its enclosure, its moats with their water, and you will see them bringing back to life a form of military power that may no longer be real, and is emphatically allegorical. More than thirty years after the construction of the last fortified castles was completed, these features serve as unmistakable architectural citations of bygone times. In the eyes of the contemporaries of François I, they conjure up recollections of a declining universe of chivalry, universe to which the young sovereign, who was the last chevalier king, remained nostalgically attached.