But the mystery of Chambord goes far beyond the mysterious figure found only on this one castle of King Francis: why did you build such an excessive splendour in the middle of nowhere, in what was an inhospitable “desert” surrounded by swamps?

We know that the king wanted a hunting residence, where the “small band” could spend short stays, and it is true that the place was gamey. But at the same time he wanted Chambord to be a wonder given to the admiration of the world. As a result, Chambord’s reasons are not to be found in the functions to which he could have responded, but in the meanings that architecture expresses in it. In these times when analogical thought reigns, Chambord is a sheaf of allegories where politics and religion are mixed. This castle is above all an exercise in monarchical rhetoric: a king’s dream.

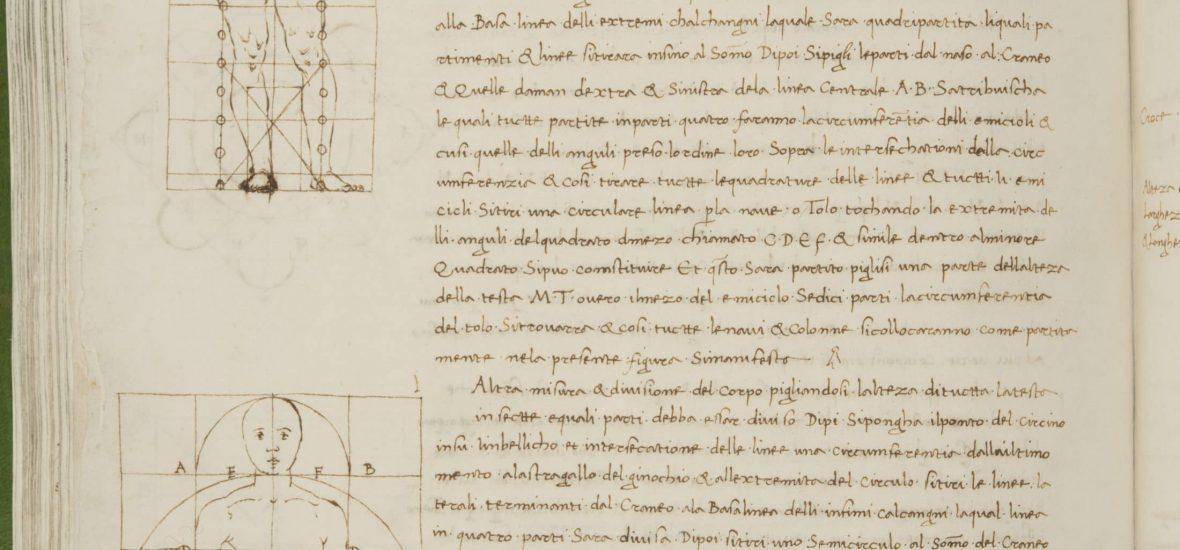

Certainly, he was not “the architect of Chambord”, first because this castle is a collective work, in which King Francis I played a central role throughout its construction, and second because, unlike Romorantin, we do not know of any drawing by Leonardo that is directly related to Chambord. On the other hand, the conversations that the king probably had with the old artist had a profound impact on Chambord’s architectural project, leaving undeniable “signatures”. This has been said of the “centered plan” and the stairs. But there is more.

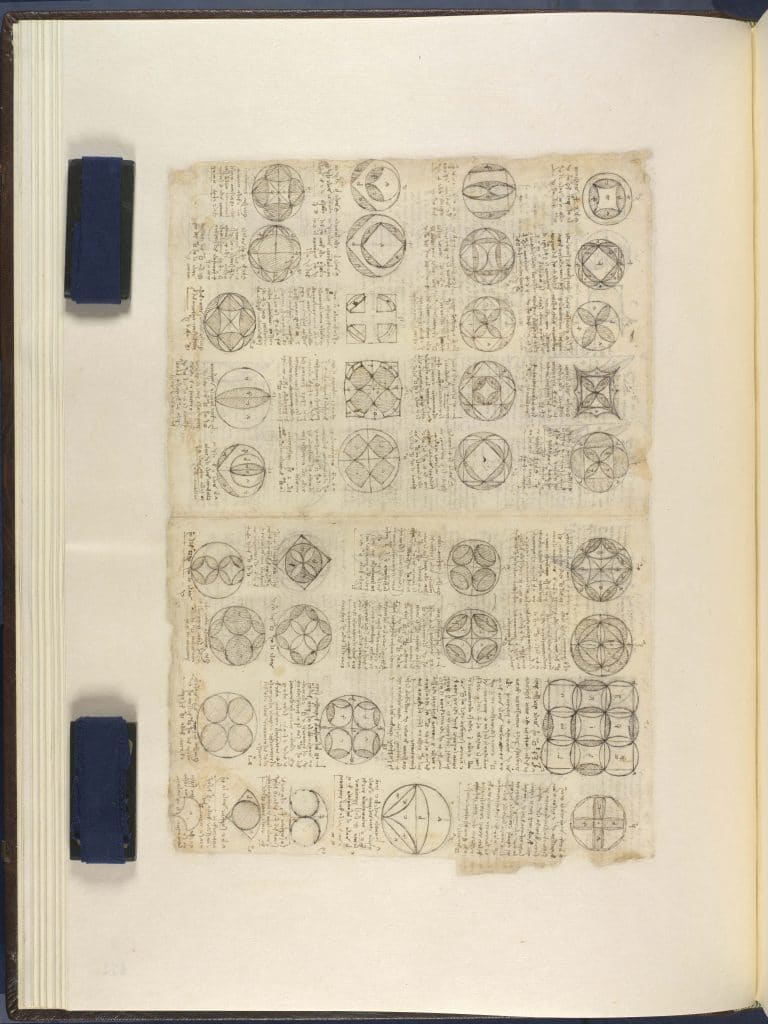

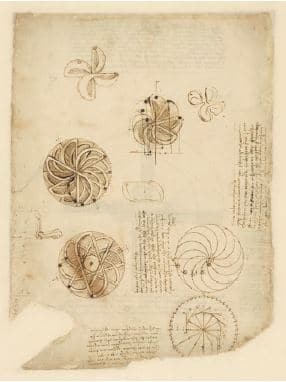

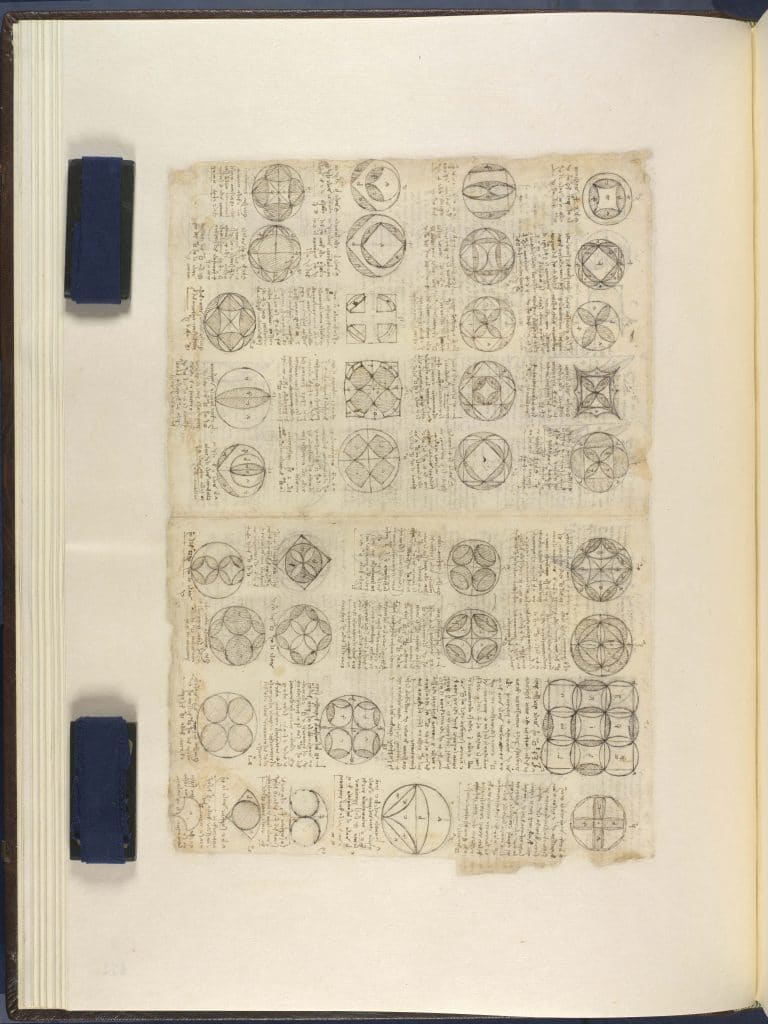

Codex Atlanticus: Distribution of the circle and squaring (Fol. 471) Leonardo da Vinci 1478-1519 Manuscript on paper Veneranda Biblioteca Ambrosiana, Pinacoteca, Milan (Italy)

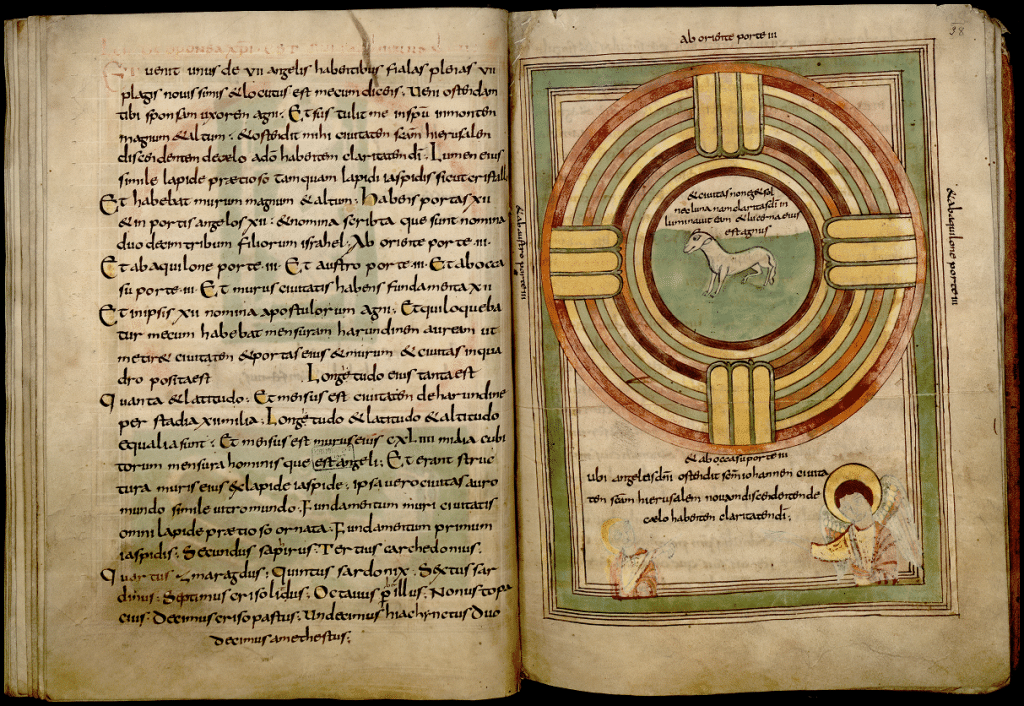

At the end of his life, given his state of health, Leonard was essentially concerned with speculative questions: the “scientist-philosopher” had taken over from the artist-engineer. He saw the world as a game of forces where fluid dynamics (water, air, blood) generated forms; he had meditated on the problem of “squaring the circle” and envisaged a dynamic geometry, where forms metamorphose into each other. His favourite object, at the centre of this meditation, was the swirling spiral: the form that arises from movement. The machine expert had become a theorist of the world’s great machinery. To understand how these themes were inscribed at the heart of Chambord’s architecture, we must now turn to what was, in 1519, the initial project. It is necessary to revive Chambord’s primitive utopia: a dungeon in “swastika”, planted in the middle of a “desert”.

At the end of the exhibition, after the final piece devoted to Leonardo da Vinci’s three original drawings, an exceptional film, created for the exhibition, will show the viewer the initial project of the castle, never realized, on which hangs the genius designer of the old Master, who died a few months before the beginning of the construction….

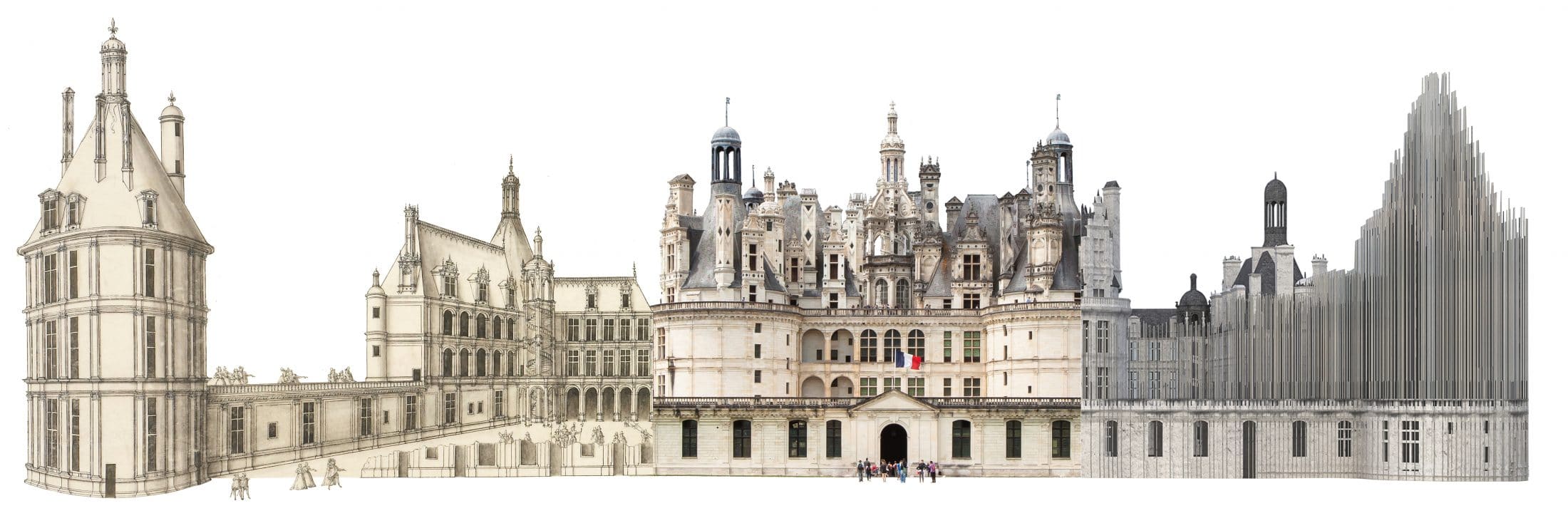

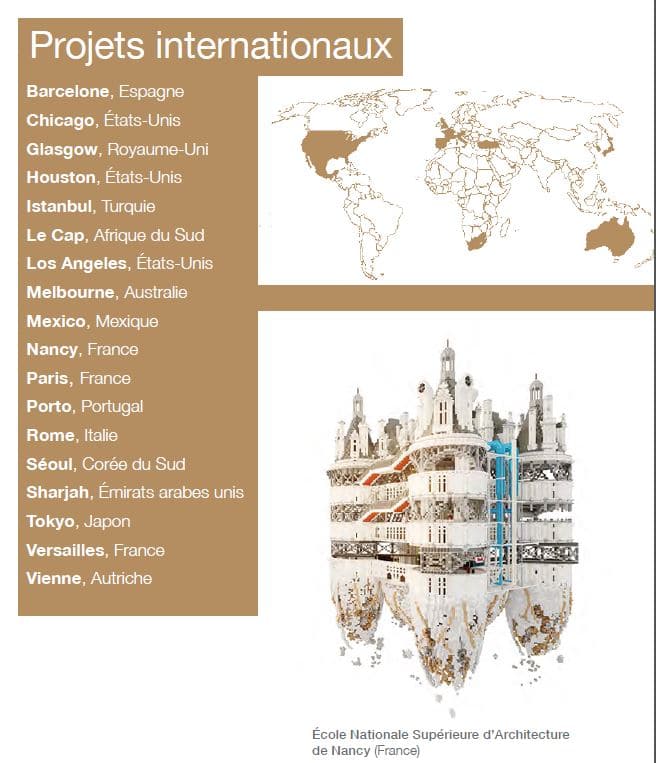

Launched in 2018, the call for projects “Chambord Incomplete” led in March to the selection of 18 universities around the world. Based on the architecture of the castle, a series of projects proposing to revive Chambord’s architectural utopia have been developed by the chosen laboratories, based on very diverse cultural and geographical positions. So many visions for a “completed” or “reinvented” Chambord, aiming to open up reflection on reality through fictional representation. Based on photos, plans, 3D surveys, computer-generated images but also, for some, visits or even stays on site, the students imagined several Chambord adapted to the scenarios they have located in 2019 or in a more or less near future. The castle of Francis I even inspired several projects at certain universities, which will present a selection or all of them.

Launched in 2018, the call for projects “Chambord Incomplete” led in March to the selection of 18 universities around the world. Based on the architecture of the castle, a series of projects proposing to revive Chambord’s architectural utopia have been developed by the chosen laboratories, based on very diverse cultural and geographical positions. So many visions for a “completed” or “reinvented” Chambord, aiming to open up reflection on reality through fictional representation. Based on photos, plans, 3D surveys, computer-generated images but also, for some, visits or even stays on site, the students imagined several Chambord adapted to the scenarios they have located in 2019 or in a more or less near future. The castle of Francis I even inspired several projects at certain universities, which will present a selection or all of them.